Putin’s play in Ukraine gave China a tough hand with the US and Europe. What are Beijing’s choices now?

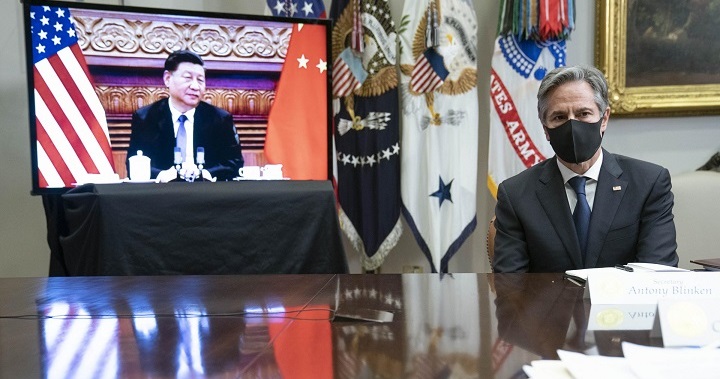

On March 18, the first major video summit between the US and Chinese presidents Joseph Biden and Xi Jinping took place. According to the official communiqué, Xi explained that China is for peace and peaceful conflict resolution. In any case, Xi asked for assurances on Taiwan.

Biden replied that the American position on Taiwan had not changed and warned Xi that there would be consequences if China helped Russia at this time.

There is distance between the two countries; it is clear from the statements on Taiwan that the positions are not really aligned. But in a sentence from Xi—”the development of the situation in Ukraine up to this point is not something China would like to see”—there is a masterwork of Chinese diplomacy.

Basically, to the Americans, he says: I do not support the ongoing bloodbath and I distance myself from it. To the Russians, he says: I could have accepted it if you took Ukraine in a single stroke, but since you have now made a global mess, I can only wash my hands of it. To the Chinese, he says: the Russians have gone too far; we can no longer stay with them.

The phrase plus the US warning is a signal to Putin while he is suffering unbearable losses on the battlefield and, so far, has failed to take the big cities.

Russia is losing Chinese political and economic support, and is more isolated. Then, either it reaches a negotiated agreement soon, allowing an orderly withdrawal, or in a little while, perhaps galvanized by successes and new weapons, the Ukrainians go on the counterattack and the Russians may run with their tails between their legs.

Beijing is lucky today that the Russian invasion of Ukraine has moved the political limelight away from China. Still, it is a small consolation because the war raises broader issues. China is now bogged down in a tough position.

It can’t cut Russia loose, because that would hasten President Vladimir Putin’s rout in Ukraine, possibly starting his political demise and maybe even the disintegration of Russia. It can’t hold Russia’s burden too long, because it could drown China with its downfall.

In the March 14 meeting in Rome between China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi and the US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, perhaps China tried to “sell” America its support for Ukraine in return for a US pledge to back China’s position on Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and Tibet. But it seems that Sullivan turned it down, arguing that the invasion of Ukraine was a matter of principle not open to realpolitik bargains.

US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken argued[1]: “China is already on the wrong side of history when it comes to Ukraine and the aggression being committed by Russia. The fact that it has not stood strongly against it, that it has not pronounced itself against this aggression, flies in the face of China’s commitments as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council responsible for maintaining peace and security. It’s totally inconsistent with what China says and repeats over and over again about the sanctity of the United Nations Charter and the basic principles, including the sovereignty of nations. And so, we’re looking to China to speak out, to speak up, and to be very clear. Second, of course, if China actually provides material support in one way or another to Russia in this effort, that would be even worse. It’s something we’re looking very carefully at. But I think this is doing real damage to China reputationally in Asia, in Europe, in Africa, and other parts of the world—something it has to pay a lot of attention to.”

These statements are strong alerts for China. Beijing is in a conundrum.

Moreover, the bad military performance of Russian troops in Ukraine is a wake-up call for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Russia has fought continuously for at least the past 20 years and despite that they are faring poorly facing Western-trained volunteers.[2] How would the Chinese do in analogous circumstances given that the Chinese last fought a real war over 40 years ago against Vietnam? Are their weapons much better than the Russians’ ones?

A few days for Putin

There isn’t too much time for China to make a stand. Within a couple of weeks, Putin will have to decide whether to attack Kyiv, bomb it, and turn it into a new Stalingrad of Ukrainian resistance, or wind down the conflict and seek a way out.

Both choices are dishonorable. Nations are made out of blood. Or better, they are made of a history with stories of blood and sacrifice. Russia is making sure that Ukraine will emerge out of this war—winning or losing, it doesn’t matter—as a nation born out of a bitter confrontation with Russia.

The political geography of Europe changes as Mittel Europa becomes wider and Russia is pushed further east. Russia will then likely be saddled with guilt because of the invasion.[3] This to Moscow is much more than the USSR’s disintegration.

That happened in pursuit of an unattainable, cruel, and yet somehow noble dream: communism. It was a systemic failure, evidence that real socialism didn’t work and could not work. This time failure occurred in pursuit of heartless and superficial expansionist delusion propped up by half-baked neo-19th-century racist theories. There will be little to cry over after the dust settles in Kyiv.

China is dragged in the middle of all of this. Last week the Chinese market tumbled following fear of possible sanctions, new COVID outbreaks, the announcement of the breakup of the big tech companies, global economic downturns, a rise in commodity prices, and overall because China is no longer hot in the stock market. The pro-market intervention by vice-premier Liu He saved the day, but left many of the wounds still open.

China is more exposed than Russia to possible western sanctions because of Hong Kong, the hundreds of companies listed abroad, and because it is more dependent on the international market for its exports and imports.

This can be a nightmare coming true. For a long time, we were worried about the outbreak of war around China,[4] the adversary of the United States and several Asian countries, and the source of the epidemic that has been dogging the world for the past two years.

The assumption was simple: After a major plague, it is easy for conflict to flare up. This has often been the case in history, and perhaps this is because repressed and unexpressed tensions in the face of such a plague in the sky have an outlet and are channeled into a conflict among men, almost as if to punish some for the evil that has struck all.

Then it was compounded by fear of war around Ukraine.[5]

The reason was still simple: Putin had massed over 100,000 soldiers on the border and needed a political success to justify such a costly move. But Putin did not achieve his goal, nor did the Ukrainians bend as time went on. Hence, the number of soldiers on the border increased, raising the stakes of the Russian gamble.

At this point, especially after the pro-Russian coup in Kazakhstan in early January, Ukraine would have to fold, or there would be an attack. But Ukraine had not bent with 100,000 troops on the border; 200,000 would not have made a difference, especially since “nationalist” rhetoric in Ukraine had swelled in parallel with the increase in Russian troops.

In this clash of rhetoric in Ukraine and Russia, only the results of an invasion could decide which of the two narratives had made a greater dent in the hearts of Ukrainians and Europeans. The Ukrainian position was then supported by Poland, the Baltic states, and Romania.

Where China stands in Europe

These states were concerned that an eventual Russian invasion of Ukraine would open up all the most sensitive dossiers in Ukraine itself to Russian aims and endanger their independence. The unresolved issue of Transnistria, on the border with Romania, and that of the land corridor linking the Kaliningrad area separating Poland and Lithuania had somehow more strategic value than a pro-Russian government in Kyiv.

Moreover, the American government had been trying for years a form of dialogue with Moscow to obtain its political support “against China.” However, the Russian coup in Kazakhstan was the last straw. To the US and the former Soviet countries, that coup showed that Moscow did not want neutral countries on its borders but satellites. At that point external support for Ukrainian nationalism strengthened Kyiv’s resolve and cornered Putin.

The latter would have lost face, putting his position at risk if he had withdrawn. He would also have been at risk if he had hesitated because he would have appeared indecisive internally. From his point of view, under these conditions, the only reasonable choice was to go ahead and attempt the gamble of invasion.

Here there was another possible error of judgment in thinking that Ukraine would quickly back down and surrender to Russian troops. Moreover, Moscow expected that Europe would be divided and helpless in the face of the invasion, and that in America, the Trump front, then rising in the electoral polls, would stymie and condition the administration.

Exactly the opposite happened. Today, it is unclear whether this mistake came from Putin himself or his intelligence apparatuses underestimated the reactions of Kyiv, the EU, and the US.

On March 11, Putin began a purge of his intelligence services blaming them for the mistakes. This purge could perhaps open the space for a way out. If Putin was deceived, he is innocent and can possibly remain in power.

The question remains open as to what Russia’s position might be after the failure in Ukraine. Indeed, it is not clear whether Putin, with the excuse of the deception suffered, could reopen to the West or continue the internal repression policy that will put him at the head of a country with a war economy.

This in turn will put Moscow’s leadership in conflict with the oligarchs who do business with the West and with Russia’s new middle class, happily emerging from decades of Soviet misery. It also places a question mark over what relations Russia will be able to develop with China.

If Russia is to survive economically, in a situation of repression, it will have to establish a de facto servile relationship with China, but this raises ancestral historical fears in Russia. As Sergei Eisenstein’s Stalin-era film Ivan the Terrible recounted, Russia was born with the expulsion of the Mongols from Moscow.

About two centuries later, Russia began to become great with Peter the Great in his push for expansion into Siberia, again in opposition to Mongol populations, which then had invaded India (the Mughals) or were conquering China (the Manchus) and were therefore distracted from Central Asia.

Returning today to the protection of the Chinese “Mongols” to survive is almost equivalent to denying 500 years of history and the very identity of Russia. In addition, there are real and concrete fears among the populations in Siberia of an advance of the Chinese in those immense territories, historically under a “Mongolian-Turkish” aegis, and where today the demographic and economic power of the Chinese looms over an almost deserted land.

China itself could be afraid that a too-close relationship with Russia could create a backlash in Russia itself and Central Asia.

In addition, a more pro-Chinese Russia would distance the historically strong relationship with India and push it more toward Japan and the United States, helping to weld a siege-line around China.

Another possibility is that Russia changes direction and sides more with the West—a nightmare for Beijing. Yet another option is that a political crisis in Moscow would create a process that would lead to the disintegration of Russia itself, as happened with the Soviet Union.

These are medium- to long-term scenarios; however, for the moment, let’s take a step back and think about the short term.

Besides, if today Europe follows the US on Ukraine and Russia, tomorrow it will be easier for Europe to follow America on its policy on China. Yesteryear was a different situation.

Ukrainian global spin-offs

Beyond the war in Ukraine, the conflict generated two crises, one concerning gas and energy supplies to Europe and another concerning grain supplies to the world. Russia supplies about 40% of the gas to Europe; Russia and Ukraine are significant grain exporters.

The scarcity of these raw materials sets in motion mechanisms of appreciation of the entire world value chain and thus creates the conditions for possible economic crises, then social, and then political. In reality, gas is abundant in the world and countries such as Canada and the United States can replace the grain supplies of Russia and Ukraine.

The problem is only time. Changing supply lines is not like turning a light on and off in a room. It takes months, maybe a couple of years, to fix them. In the meantime, it’s possible that these failures could set in motion social and political upheavals in developing countries. For example, some striking cases could be Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia.

In 2011 the increase in the price of wheat ignited the dust of political revolutions that led to the end of the Mubarak regime in Cairo. Today, it is unclear what could happen, but the possibility of waves of refugees from Africa toward Europe is growing.

In addition, Russian political difficulties in Ukraine put a question mark over the Russian presence in three key scenarios: Syria, Libya, and Mali. A war could flare up there if the Russians were to weaken either in one or all of these areas. Of course, the most dangerous scenario concerns Syria, where a blowback would risk reigniting Iraq and the Kurdish issue and alarming Israel, Turkey, and Iran.

Finally, now that Moscow is losing, it may try to gain cards for a global negotiation by “throwing it in the wind.” These days, North Korea is preparing missile tests and has conducted seven since the beginning of the year, since the Ukraine crisis was ongoing.

Iran on March 12 attacked Kurdistan, and the war in Yemen is back on full gear. It is unclear whether these groups are taking advantage of the general distraction or whether Moscow encourages chaos to get distraction from Ukraine. Either way, chaos calls for chaos.

The most delicate issue concerns China, the target and the rival of the new cold war underway in Asia and now in the world. China has been put and has put itself in a challenging position in the medium term. For a short time, China has had immediate relief from American pressure.

This is a phenomenon similar to what happened in 2001 with September 11. After the attack, America completely changed its attention and moved from a confrontation with China to Islamic terrorism. This change of direction was not automatic and immediate.

In the beginning, some people in America thought that the attack had been planned with Chinese help or inspiration since a book[6] by colonels Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui had defended the use of asymmetric war and had seen the future danger in al Qaeda. At that time, China immediately started collaborating actively and decisively with the United States for everything concerning Afghanistan and Muslim terrorism.

This time, however, it was not so. China did not immediately reorient itself for collaboration with America and Europe against the aggressor, this time Russia. On the contrary, to this day it tries to maintain an equidistant position between Russia and Ukraine, internally crediting the thesis that the origins of the conflict are to be found in the expansion of NATO to the east. This puts China in an objectively tough situation. Particularly if, as it seems, Putin loses the war. How will Beijing justify the political defeat of its ally?

Will it have reflections, and if so, which ones, in the political debate in Beijing? Beijing had bet on, and believed in, the inevitable decline of American power, and had aimed to separate the US from Europe.

Today, the American administration has isolated Putin, once considered a political and strategic genius, and has strengthened transatlantic relations, getting European countries to accept Washington’s leadership with more conviction.

Europe’s intelligence capability failed. Everyone in Europe was skeptical about the possibility of the Russians invading Ukraine, while America continued undaunted to say that there would be an invasion.

Lonely China

There are signs of second thoughts in Beijing. An essay by Hu Wei,[7] published on March 10, goes in this direction, but it still seems too little and does not represent the clear will of the leadership.

China thinks it still has time to observe, reflect, and perhaps mediate between the US and Russia. But in reality, the war is already politically over. Russia has lost politically, beyond the tragic continuation of the fighting and the cruel trail of blood on the field.

China, therefore, comes out of this crisis more isolated and defeated in its cultural assumptions that guided the political choices in the last 15 to 20 years. Russia is not a strategic superpower, America is not in decline, Europe follows America, and Asia sees the confirmation of American global leadership, strengthening its anti-Chinese determination.

Finally, if the invasion of Ukraine fails, any attempt to invade Taiwan will flop. These assumptions galvanize the anti-Chinese pushback in Asia, fan the flames of the Cold War, and leave China more isolated. The consequences are still difficult to calculate.

There are indeed two roads ahead for Beijing: one is to begin a 180-degree turn and seek a new relationship with its neighbors and the West; the alternative is to close itself behind a new bamboo curtain and weather the current storm.

Both choices have advantages and disadvantages for the Chinese leadership and pose different challenges to Europe and America. The most likely is closure because the currently chosen policy line more easily justifies it. The difficulty with this route is that it starts with an admission of defeat and involves imposing a long-term siege on the country.

There is a silver lining in all of this. The longer war drags on, the more time Beijing has to think. And still, the higher the political interests compound for some reckoning.

[1] See https://www.state.gov/secretary-antony-j-blinken-with-steve-inskeep-of-nprs-morning-edition/

[2] See https://www.aol.com/news/exclusive-secret-cia-training-program-090052594.html

[3] See https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/16/opinion/russia-ukraine-putin.html

[4] See for instance http://www.settimananews.it/informazione-internazionale/us-china-war-real-possibility/ or http://www.settimananews.it/informazione-internazionale/plagues-liberal-society-and-the-future-after-covid/

[5] http://www.settimananews.it/informazione-internazionale/german-ukraine/

[6] Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui, Unrestricted Warfare, People’s Liberation Army Literature and Arts Publishing House, 1999.

[7] https://uscnpm.org/2022/03/12/hu-wei-russia-ukraine-war-china-choice/

Grazie Francesco per questo articolo, denso e preciso. Mi lascia costernata l’idea, o meglio i fatti che stanno accadendo. Siamo alla vigilia di una guerra mondiale? Sicuramente siamo alla distruzione di donne, bambini e esseri umani in genere, stiamo distruggendo città bellissime: quale demone di domini muove i cuori e le menti? Mi dirai che così penserebbe tua madre. Non sono una politologo, osservo e soffro come molti e molte.

Grazie, come vedi ti seguo e ti leggo,

sr. Giuliana

“It’s totally inconsistent with what China says and repeats over and over again about the sanctity of the United Nations Charter and the basic principles, including the sovereignty of nations.”

US says it’s keeping to the “International Liberal Rules Based Order” which grossly contradicts the Charter of the United Nations. You cannot find in the Charter a Chapter on the rights and duties of a Hegemon. Neither of course in the Rules of ILBRO because these are not written down and are changed as US sees fit.

The writer thinks that the only way to fight a war is the way US practices that “art”. Russia is now operating in a country that will remain a neighbor and with countless family relationships across the common border. It makes then sense not to try to kill as many people as possible, or even as many soldiers as possible and to do as little damage to cities, towns and infrastructure as possible. Russia has surrounded many of the cities and a large part of the Ukrainian army and is now waiting until supplies run out.

Ukraine after the Maidan coup is not an independent country but a satellite of US. It is also responsible for shooting down MH17. The trial in the Netherlands is based largely on “evidence” manufactured by Kiev – it is a member of the Joint Investgation Team. “Unfortunately” some has been made by people who didn’t understand the way the war was fought and thus represented rebels wanting to use Buk missiles that would have been quite useless because these would have been extremely vulnerable to long range artillery attack without contributing to the defense against air attack.

Francesco Sisci… I have been following your writing over these many years since JP introduced us and must say that this is one of your finer pieces. My only reservation is your stating that the USA is not in decline. I am afraid that the vaunted American Empire is very much in decline and that Putin’s disastrous move into Ukraine simply puts off the inevitable. President Biden is doing his nuanced best to avoid World War III but he is being openly challenged by the Putin wing of the Republican Party and his Democratic Party appears headed to a rout in the elections later this year. My mother country is hopelessly divided with a schism so deep that even tip toeing to a reconciliation of the political polarity is nigh on impossible. With 12 years now living in China, I have observed the dissolution of the political class in the USA with neither side offering the increasingly desperate Americans any respite from the economic devastation wrought by years of slavish adherence to neoliberal policies. While an actual civil war is still a couple of years away, we see the run up to armed clashes already occurring as the pandemic, inflation and irreconcilable differences erode the pillars upon which a functional democracy requires.